December 29, 2020

How the Collision of Consumer Demand and Capacity Constraints of 2020 Impact Economic Recovery

How the Collision of Consumer Demand and Capacity Constraints of 2020 Impact Economic Recovery

As the tumultuous year winds down, it’s clear that 2020 tested the agility of major economies like none in recent memory. By looking at the results of those tests, we can draw insights regarding how quickly we will recover from the year’s shocks.

When the pandemic first struck, there was optimistic talk of a V-shaped recovery. While it was clear that the initial economic impact would be drastic, there was hope that the economy could pick up where it left off after a brief hiatus.

Very quickly, though, we saw glaring issues with capacity constraints. The infamous toilet paper wipe-out of the spring had less to do with supply chain failures and more to do with how to accommodate rapidly shifting demand. As people stayed home from work, orders shifted from large rolls of office-building toilet paper to small rolls for homes—which require different production processes. This meant that relatively stable toilet paper consumption masked giant swings in demand–and there were capacity constraints on how quickly production and distribution for home bathrooms could be ramped up.

The imbalance was really emblematic of what was happening in the broader economy. As notable as the aggregate shifts in spending and retail were, they masked even bigger shifts at a disaggregated level.

To be specific, compare US real personal consumption expenditures in November with those on the eve of the pandemic’s impact, back in February. Overall, monthly personal consumption seemed to rebound fairly well. In April, it had fallen by 17.9% from February, but by November, it was down only 2.7%. A wild ride, but we ended up reasonably near the starting point.

However, a more detailed breakdown of consumption doesn’t look so smooth. For that same comparison of November to February, durable goods consumption was up 12.0% and nondurable consumption up 4.8%. But services consumption dropped 7.1%. US consumers weren’t going out to restaurants or sporting events; they were buying recreational goods and vehicles instead.

The way they were buying those goods was also shifting. According to MasterCard SpendingPulse data, comparing the 75 days leading up to Christmas in 2020 versus the year before, retail sales (excluding autos and gas) were up 3.0%, but e-commerce sales jumped 49%.

When declining sectors contract more readily than favored sectors expand, an economy is slow to get back to its potential. What’s unusual here is that it is more common to see capacity constraints play out during product fads—not across broad swaths of the economy.

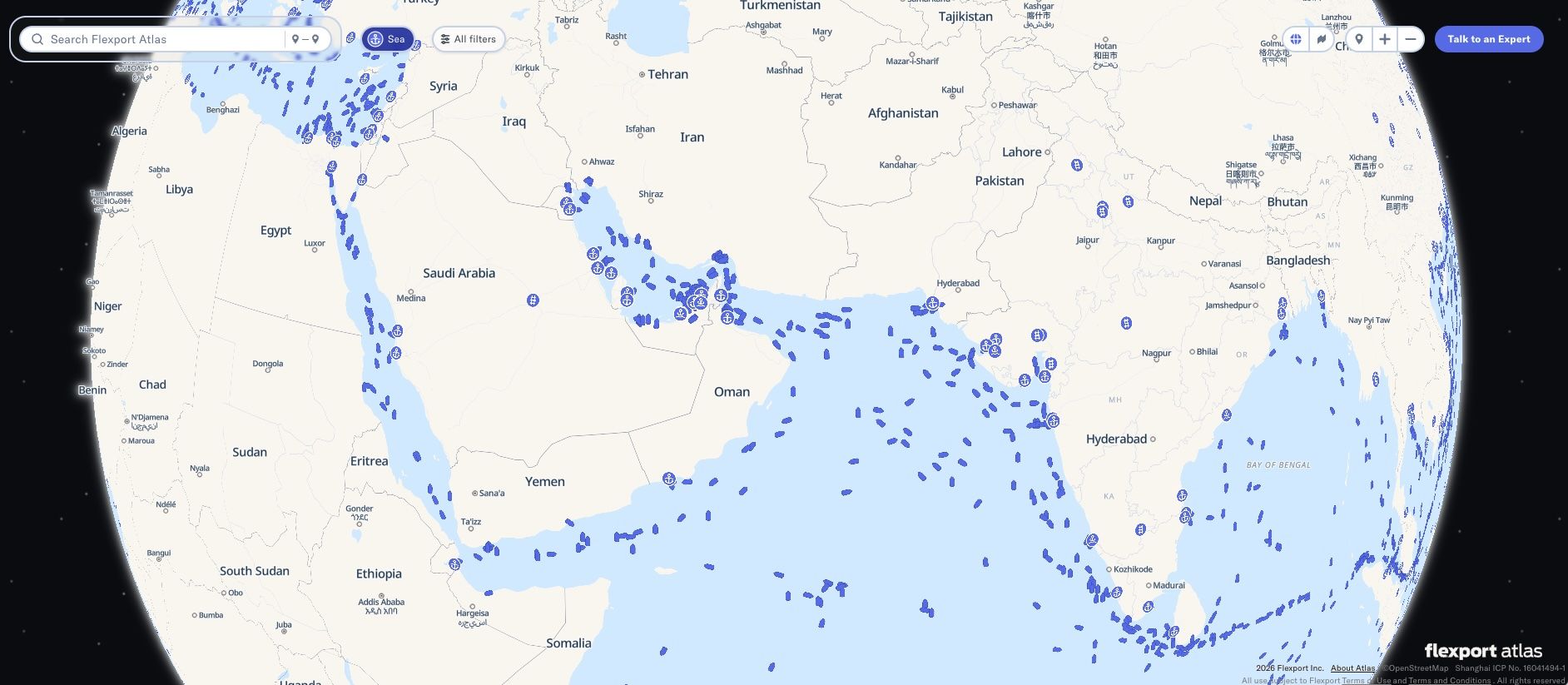

Such shifts leave some facilities idled, while others endure strains in production and logistics as they try to meet dramatically increased demand. For ocean transport, there have been huge pressures to try to find containers; move them across oceans on a limited number of ships; unload them at ports; store their contents in warehouses; and get them to customers. The air cargo situation has been at least as difficult because of a de facto capacity cut; reduced demand for passenger travel cut flights—significantly reducing cargo space. The result of these capacity constraints has been historically high prices.

The most straightforward implication of these capacity constraints is a limitation on how quickly the economy can recover.

The upheavals of 2020 pose difficult investment questions for those overseeing supply chains and logistics. Is it worth investing in additional capacity? When the pandemic finally recedes, will these large swings in consumer behavior reverse themselves? Or, is this the new norm?

These are the questions I’ll be exploring—and blogging about—as 2021 unfolds. In the meantime, best wishes for a happy and healthy new year.

About the Author

More from Flexport

![GettyImages-723523781 1199x800]()

Blog

The End of the EU’s Duty-Free Exemption for Low-Value Goods: Timelines, Upcoming Changes, and Impacts on Ecommerce Brands